On rough drafts

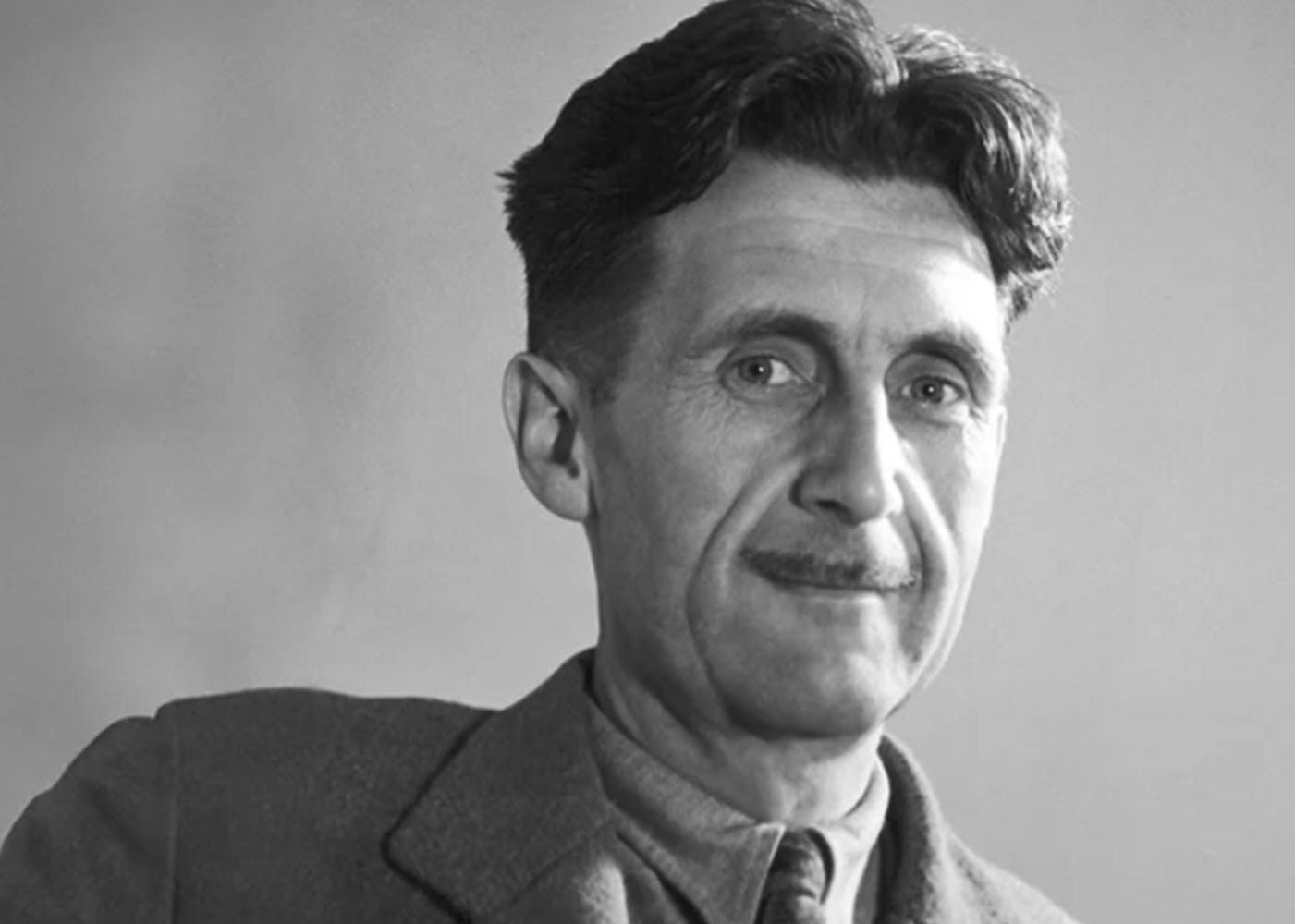

GEORGE ORWELL | “The rough draft is always a ghastly mess bearing little relation to the finished result, but all the same it is the main part of the job.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

There’s a wonderful passage in the Richard Curtis film Four Weddings and a Funeral, in which Charles (the Hugh Grant character) confesses his feelings to Carrie (Andie McDowell) for the first time:

Charles: Ehm, look. Sorry, sorry. I just, ehm, well, this is a very stupid question and … , particularly in view of our recent shopping excursion, but I just wondered, by any chance, em, eh, I mean obviously not, because I guess I’ve only slept with nine people, but – but I – I just wondered … ehm, eh, I really feel, ehh, in short, to recap it slightly in a clearer version, eh, in the words of David Cassidy in fact, eh, while he was still with the Partridge family, eh, “I think I love you,” and eh, I – I just wondered if by any chance you wouldn’t like to … eh … eh … No, no, no of course not … I’m an idiot, he’s not … Excellent, excellent, fantastic, eh, I was gonna say, lovely you see you, sorry to disturb … Better get on …

Carrie: That was very romantic.

Charles: Well, I thought it over a lot, you know, I wanted to get it just right.

Charles will have further opportunities to get it just right; in fact, the whole movie is more or less about people making ghastly messes in the service of trying to get it just right.

Life, it seems to me, is more or less about that.

Most people who set out to be writers stumble right out of the starting gate, because they are unwilling to write a ghastly first draft. Or, if they do, they are then reluctant to admit that it is only a draft and will need a vast amount of rewriting to become what it was meant to become.

And here you have the #1 thing that halts aspiring writers in their tracks, preventing them from ever writing what it was they felt the urge to write: They scribble out a few paragraphs, look at what they’ve done, go, That sucks, get discouraged, and quit.

And that is a shame. Maybe even a tragedy.

The hard thing about it is that they’re probably right. It does suck. Just ask George Orwell. And Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner, two more of the twentieth century’s literary giants. And E.B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web, the most popular children’s book of all time.

“The first draft of anything is crap.” — Ernest Hemingway

“Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but it’s the only way you can do anything really good.” — William Faulkner

“The best writing is rewriting.” — E.B. White

Yes, it’s true: Orwell and Hemingway and Faulkner and White all wrote first drafts that sucked.

So here is what the aspiring writer needs to know: The fact that your first draft sucks does not mean you’re failing; it means you’re being a writer.

And the reason all that quitting is a tragedy is that couched within that awkward, clumsy, overwritten ghastliness there lurks the seed of something great.

In my coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship, I have an entire module called “Write Drunk, Edit Sober.” Follow the impulse, get it down, don’t try to get it just right. Let it be a ghastly mess. As Faulkner points out, it’s the only way you can do anything really good.

The same thing happens in our lives. We do our best, and sometimes the result is a ghastly mess.

I reflect on this in the conclusion to How to Write Good:

There are times when the rewrite feels painful, when you stare at the Editor’s cruelly wise suggestions and resist them with every fiber of your being. Standing in bankruptcy court, my beloved business a smoking ruin; standing in divorce court, my marriage in tatters; standing in a hospital corridor, my child gone; watching the proud accomplishments turned to sand and the cherished things ripped away—these and many more moments I’ve spent staring at pages and pages of my life covered in the red ink of deletes and cross-outs.

And has the story turned out the better for it? I can’t honestly say, because I’m still in the middle of the rewrite, but I have to believe that it has; I have to trust the Editor.

There’s a line in The Go-Giver where the wise old colleague Gus tells Joe:

“Sometimes you look foolish, even feel foolish, but you do the thing anyway.”

Charles no doubt felt as foolish as he sounded. But he won Carrie’s heart.

My February wish for you:

That you take a few moments every day to consider times you have got it just wrong, even made a ghastly mess; understand that you were doing the best you could at the time, that it was a rough draft; then forgive yourself — and move on to the rewrite.

About the writer

George Orwell is most familiar to modern readers as the novelist who wrote Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, but for most of his life he was known for his hard-hitting journalism, social commentary, and critical essays.

Born Eric Arthur Blair in 1903 to a British family, the future novelist was packed off to boarding school at the age of eight and hated the experience (“beastly,” as he recalled it) until he landed a scholarship spot at the prestigious boys’ school Eton at age 14. Blair was a dreamy, thoughtful student with a spotty academic record but a penchant for language. His first poems were published in the local paper at the age of 11, as World War I had just begun raging across Europe:

Oh! give me the strength of the lion,

The wisdom of Reynard the fox,

And then I’ll hurl troops at the Germans,

And give them the hardest of knocks.Oh! think of the War lord’s mailed fist,

That is striking at England to-day;

And think of the lives that our soldiers

Are fearlessly throwing away.Awake! oh you young men of England,

For if, when your Country’s in need

You do not enlist by the thousand,

You truly are cowards indeed.— Eric Arthur Blair (George Orwell), age 11

At 18, the Great War now long concluded, he did enlist, though not in the way he’d imagined at 11: with his poor academic record and family’s thin finances dimming his university prospects, his family packed him off again, this time to Burma to join the Imperial Police, in which he served for five years before quitting to become a writer.

At this point the young Blair made a decision that would set his philosophical and literary compass for the rest of his life. Inspired in part by Jack London, a writer he greatly admired, he set out to learn about life in the poverty-stricken neighborhoods of East London and later Paris. Adopting the alias “P.S. Burton” so as not to embarrass his family, he lived as a vagrant on and off for the next five years. The experience came to an abrupt end when he fell seriously ill and was robbed of all his money.

Returning to his parents’ home to recuperate and write, he produced the typescript of what would become his first published book, Down and Out in London and Paris.

It wasn’t easy. According to friend and biographer T.R. Fyvel, Blair struggled mightily to get his experiences onto the page in a way that lived up to his expectations.

His crucial experience … was his struggle to turn himself into a writer, one which led through long periods of poverty, failure and humiliation… . The sweat and agony was less in the slum-life than in the effort to turn the experience into literature. — George Orwell: A Personal Memoir, T.R. Fyvel

The manuscript was rejected by several publishers, including Faber & Faber, whose editorial director (a fellow by the name of T.S. Eliot—yes, that T.S. Eliot) declared, “We did find it of very great interest, but I regret to say that it does not appear to me possible as a publishing venture.”

As Stephen King would do forty years later with his first draft of Carrie, Blair threw it in the trash, where it was fished out (as King’s wife Tabitha would do with Carrie) by a family friend, who took it to a literary agent, who in turn showed it to the publisher Sir Victor Gollancz, an avid supporter of pacificist and Christian socialist causes. Gollancz enthusiastically agreed to publish the book — but only after removing some “bad language” and objectionable passages, one of which Blair protested was “about the only bit of good writing in the book.”

Yes: in his very first book, George Orwell had to murder his darlings.

One more transformation had to happen before the book could be ready for publication: Blair did not want to publish under his own name and kicked around a number of possible pseudonyms until settling on an alias that evoked one of his favorite bucolic settings, the River Orwell in Suffolk.

“George Orwell” became the nom de plume he would stick with for the rest of his life.

After Down and Out, Orwell continued researching and writing about poverty and the bleak living conditions of the working class, a career path that brought him to the attention of the London police force’s Special Branch, which kept him under surveillance and investigation for more than a decade.

In 1936, concerned about the militaristic rise of Francisco Franco in Spain (which was supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy), Orwell enlisted to fight in the Spanish Civil War, where he saw a significant amount of action. At one point he was shot through the neck by a sniper’s bullet, passing fractions of an inch from a main artery. At 6’ 2” a head taller than his Spanish comrades-in-arms, the British recruit had been warned not to stand up.

But then, Orwell never did pay much heed to warnings not to stand up.

When World War II broke out in Europe he submitted his name to England’s Central Registrar but was declared medically unfit for service. He did manage to gain a spot in the British Home Guard, where he experienced the Blitz first-hand and ran a broadcast program for the BBC designed to counter Nazi propaganda. And over the last few years of the war he also wrote a political fable, inspired in part by the Hans Christian Andersen tale The Emperor’s New Clothes (his own adaptation of Andersen’s story aired during Orwell’s last week at the BBC).

He entitled his new fable Animal Farm — and it won him near-instant, world-wide acclaim, making him one of the most sought-after writers of his era.

After the war a friend lent Orwell the use of a remote farmhouse in the north of Scotland to work on his next book, where he endured one of the coldest winters of the century, increasingly worsening health, and an epic struggle to produce a completed manuscript by the deadline his publisher had set.

In May of 1947 he wrote to his publisher:

“I think I must have written nearly a third of the rough draft. I have not got as far as I had hoped to do by this time because I really have been in most wretched health this year ever since about January (my chest as usual) and can’t quite shake it off.”

To which he added,

“Of course the rough draft is always a ghastly mess bearing little relation to the finished result, but all the same it is the main part of the job.”

The author struggled on; by December the following year the typescript was finally delivered to the publisher, and Orwell returned to England where he promptly checked into a TB sanitorium. Nineteen Eighty-Four, which would become his most famous work, was published in June of ’49. The following January, at the age of 46, Orwell finally succumbed to complications from tuberculosis.

There is so much more remarkable detail I would love to share about these final years; for a riveting account of the author’s desperate post-war quest to complete his most famous work, check out this 2009 article, “The Masterpiece That Killed George Orwell” in The Guardian.

Arthur Koestler, famed author of Darkness at Noon, said of Orwell that his “uncompromising intellectual honesty made him appear almost inhuman at times.”

The author and American political pundit Ben Wattenburg wrote that “Orwell’s writing pierced intellectual hypocrisy wherever he found it.”

And British historian Piers Brendon called Orwell “the saint of common decency who would in earlier days, said his BBC boss Rushbrook Williams, ‘have been either canonized—or burnt at the stake.’”

In the year 1984, Nineteen Eighty-Four was honored, along with Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, with the Prometheus Award for its contributions to dystopian literature. In 2021, the New York Times Book Review named Nineteen Eighty-Four #3 on its list of “the best books of the past 125 years.”

Not bad for something that started out a ghastly mess.

Recommended Reading

In the extraordinarily unlikely case that you’ve never read any Orwell, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

1984 (1949), his chilling vision of totalitarianism.

Animal Farm (1945), the political fable that made him immortal.

Homage to Catalonia (1938), his personal account of the Spanish Civil War.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.