On meaning

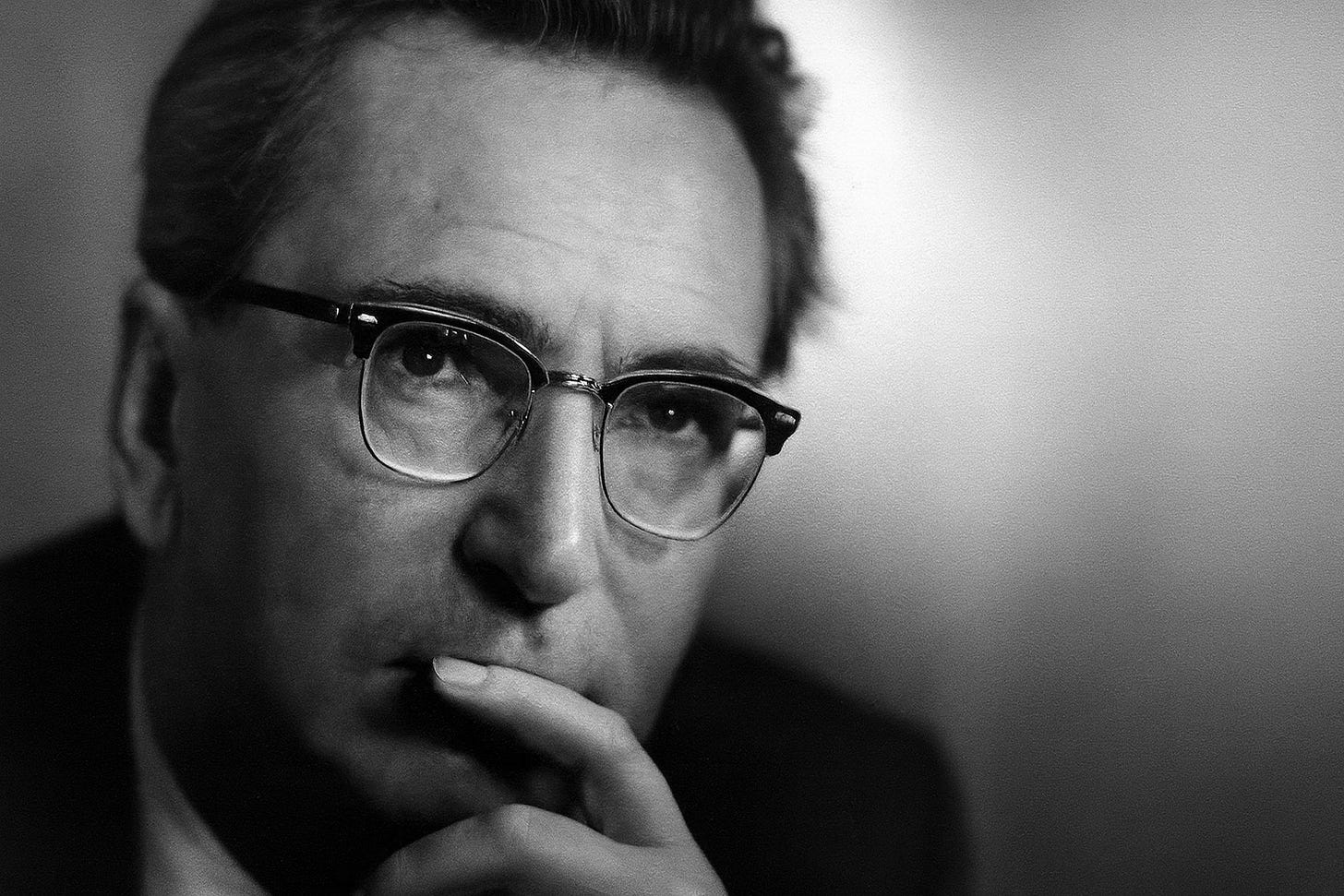

VIKTOR FRANKL | “Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

It’s winter 2009. Coming up on 6:00 pm, dusk falling, temperatures plummeting. Road conditions treacherous. I am driving east on Route 84, somewhere in New York, heading for Massachusetts and home.

As I enter a long leftward curve in the highway ahead I noticed what looks like a display of fireflies, a scatter of faint flickering lights. Brake lights, dozens of them.

The slick on the road has begun to freeze.

I pump my foot, carefully, carefully, remembering everything I know about driving on the ice, doing my best to keep a hold on my car’s reins, working the wheel, working the brake, I know how to do this, and it’s working, and it’s working, and it’s not working—

The car starts to slide. Like every other car around me. All of us hurtling together in forward freefall at 60 miles per hour, 88 feet per second.

They say your life flashes before your eyes. It isn’t like that for me, not exactly. Instead, a question flashes before me, vivid as an illuminated billboard:

Would it be okay to die?

Now I realize my car is turning a slow pirouette as it bombs another 88 feet down the highway. All semblance of control, gone.

Strangely, I feel no fear. Maybe it’s just the adrenaline. Maybe it’s something else.

“The fear of death,” wrote Mark Twain, “follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time.” Crazy Horse agreed. “Today is a good day to die,” the Lakota chief said as he rode into battle at the Little Bighorn.

Now my car has done a full 180, hurling down the highway backwards, a two-ton machine wholly at the mercy of snow and ice and the angels.

Am I okay with dying — today, right now?

And the answer comes back instantaneously —

Yes.

Yes, I’m okay dying, today, right now.

Because: Ana will know that she has been loved, well and truly loved.

Because: I have five kids out in the world, each scattered to their own time and place and circumstance, and they will go on living their lives and having their impact.

Because: The Go-Giver is out in the world, changing people, affirming people, leaving its mark. My mark.

It’s enough.

My car slams into a guardrail drivers side first, pinning me inside. Out the windshield, now facing the oncoming traffic, I see several dozen steel-and-aluminum monsters stampeding toward me. I cannot budge. I don’t even try.

One of my favorite composers, Béla Bartók, died of leukemia in a New York hospital in 1945. His final words, spoken to those close to him: “The sad thing is that I have to leave with so much to say.”

I feel the same way right now, in one sense: there is still so much more to say. But in light of that 3-second inventory I’ve just taken — Ana, kids, The Go-Giver?

Yeah. I’m okay with it.

So my question for you:

If you were the one veering off 84 East and crashing, today, right now, would you be okay leaving the planet? And if not, what would need to happen first to make it okay? (If you trust me enough to share this, REPLY HERE — I would love to read your answer!)

There is a popular bit of psychology that says we humans are motivated by two primal drives: the urge to seek pleasure, and the urge to avoid pain. Master those, the thinking goes, and you’ve mastered the levers of human behavior.

Not true! said Viennese psychologist Viktor Frankl. According to Frankl, that pain/pleasure duality is incidental to our lives, not central. So, what is central?

The quest for meaning.

Frankl famously tested his thesis while surviving his internment in Auschwitz (and Theresienstadt, and Kaufering, and Dachau), as he describes in his best-known work, Man’s Search for Meaning. For Frankl, meaning was what allowed him to live.

For me, trapped in my runaway car on an icy highway, meaning was what would allow me to die.

But it seems to me we were both saying much the same thing.

A few months before the pileup on 84E, my friend and coauthor Dave Krueger had told me something I’ll never forget:

“I believe the most basic motivation we have as human beings is to be effective, to be a cause.”

As it happens, I didn’t die that day. Miraculously, none of the two-dozen-plus cars careening toward me made contact. I eventually crawled out the passenger’s side, hoofed it 50 feet to a nearby stopped truck, and climbed up into the cab, where my hosts offered a few minutes of warmth and safety along with the observation that I was “one lucky sonofabitch.”

After a bit I climbed down and trekked back. My car was the only one that left that scene on its own steam. I hobbled to a nearby motel for the night, and got a tow in the morning.

Today Ana is still well and truly loved, my five kids have now produced five grandkids, and the two books I’d published back in 2009 have turned into 40 books and counting. Life is good. And still, so much more to say.

“Every man owes a death,” wrote Stephen King in The Green Mile. “There are no exceptions.” True enough, but death, it seems to me, is simply a punctuation mark.

The question is, what does the sentence say?

My January wish for you:

That you spend a little time every day asking, What is it that makes my life worthwhile? What gives it meaning? What matters?

About the writer

Viktor Emil Frankl was born in Vienna on March 26, 1905. A brilliant student in school, he took a high school course as a teen in Freudian theory that prompted him to write to the master himself. Freud replied, and the two struck up a correspondence. Viktor, then age 16, sent the professor a two-page paper he’d written, and Freud loved it so much he immediately submitted it to his editor, who published it in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis.

However, within a few years the teenager began questioning Freud’s approach to psychoanalysis. At the University of Vienna Medical School, he began attending seminars with the eminent psychologist Alfred Adler, who had broken with Freud more than a decade earlier. Yet he soon found himself disagreeing with Adler, too, believing that Adler had erred in minimizing people’s freedom of choice and autonomy.

Adler openly challenged his student to speak up and defend his position. The young man stood and spoke for 20 minutes. When he was finished, Adler sat stone still for a few chilling moments (“terrifyingly still,” as Frankl later recalled), and then began shouting furiously at him. Frankl was ousted from Adler’s circle and never invited back.

While still in medical school, Frankl organized a system of youth counselling centers to address the high number of teen suicides, especially among students around exam time. Sponsored by the city of Vienna, the popular program was offered free of charge to students. In 1931, the year after Frankl graduated, not a single Viennese student died by suicide.

Working with suicidal patients and those who suffered from profound grief, loss, or a sense of alienation or hopelessness would become a central pursuit throughout Frankl’s life.

After receiving his medical degree, now working as chief of the university’s neurology and psychiatric clinic, Frankl continued developing his evolving views, describing his approach as a “third school” of psychotherapy, after Freud and Adler. Here is how Harold Kushner describes Frankl’s approach in a foreword to the 1992 edition of Man’s Search for Meaning:

“Life is not primarily a quest for pleasure, as Freud believed, or a quest for power, as Alfred Adler taught, but a quest for meaning.”

In the 1940s, amid the wartime rise of antisemitism and looming threat of arrest, Viktor was thrown a life preserver: he received an invitation from the American consulate to immigrate to America, a move that would have ensured his safety. He weighed the opportunity — but couldn’t reconcile with the idea of abandoning his parents.

He turned the offer down.

Sure enough, within months he and his entire family were arrested and sent to a concentration camp, where the odds of survival (as he later noted) were 1 in 28.

Frankl’s mother, father, brother and pregnant wife all perished in the camps. The man lost everything, he said, that could be taken from a prisoner, except one thing: “the last of the human freedoms, to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

Even at Auschwitz, he observed, some prisoners were able to discover meaning in their lives, if only in helping one another through the day, and that was what gave them the will and strength to endure. As he later noted:

“Suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.”

At the time of his arrest, Frankl was already at work on a book describing his developing theories. Hoping to preserve her husband’s work, his wife had sewn the pages of his manuscript into the lining of his coat — but the moment they arrived at the camp all the prisoners’ clothing was confiscated, his manuscript lost forever.

Nevertheless, he began recreating it in his barracks, late at night, using bits of paper stolen for him by a companion.

Frankl spent the next three years in four concentration camps, including Dachau and Auschwitz.

Upon his release in 1945 he completed his book, writing out the finished manuscript in 9 days, and published it under the title A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp. He had planned to publish anonymously, feeling the work should stand on its own merit, but at the last minute gave in to the urging of friends, who persuaded him to at least put his name on the title page.

First published in English in 1959, Man’s Search for Meaning eventually gained an enormous readership worldwide. At the time of the author’s death, more than half a century after its initial publication, the book had been reprinted 73 times, translated into 24 languages, sold more than 10 million copies (today, over 12 million), and was still being used as a text in high schools and universities.

Readers in a 1991 survey by the Library of Congress and the Book of the Month Club called Man’s Search for Meaning one of the 10 most influential books they had ever read.

Among the myriad treasures in its pages:

“Don’t aim at success — the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s dedication to a cause greater than oneself.”

“A human being is not one in pursuit of happiness but rather in search of a reason to be happy.”

“Being human always points, and is directed, to something other than oneself — be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter.”

And of course, this:

“Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation of his life.”

After the war Frankl became head of the neurology department at a hospital in Vienna and established a private practice in his home, where he continued working with patients until his retirement in 1970. He died in 1997 at the age of 92, and was buried in the Vienna Central Cemetery, along with the great composers Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and Schoenberg … and within shouting distance of Alfred Adler.

Recommended Reading

If you’ve never read any Frankl, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), his world-changing memoir and psychology of survival (and this newsletter series’ namesake).

The Will to Meaning (1969), expanding his ideas of logotherapy.

Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything (2020), posthumously published lectures from 1946.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.