On limitations

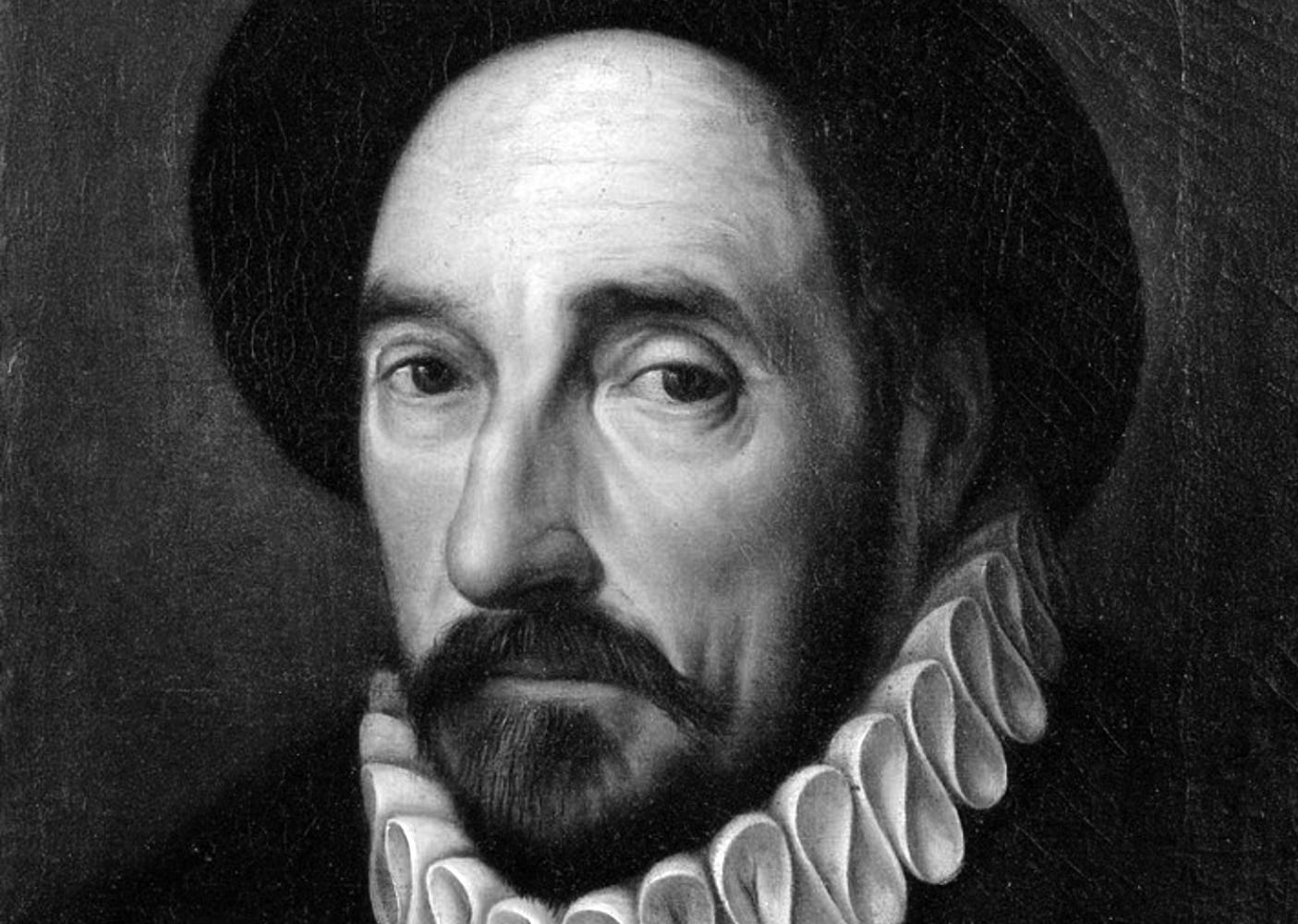

MICHEL de MONTAIGNE | “The trumpet’s voice rings out clearer and stronger for being forced through a narrow tube.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

I was born with a condition known as idiopathic clubfoot. What this meant, in my case, was that for reasons unknown, when I emerged from the bliss of gestation, both my feet were bent like horseshoes so that my toes touched my heels.

This deformity, as the doctors told my parents, meant that I would never walk.

Not, that was, unless something could be done about those feet.

The medicine of the time offered two possible strategies. One, make a surgical slice through both Achilles tendons, then reset the feet to a more normal shape (sort of like resetting a broken nose), insert pins to hold them in place, then cast them and hope the new shape takes and the tendons heal well.

The alternative would be to leave tendons intact and cast the feet in a slightly less bent position, then every six weeks cut off those casts and recast them again in progressively straighter positions, until the last cast stretched them into their final, fully straightened shape.

The first way was quick, but risky. The second would take many months.

My parents chose the second path. I wasn’t free of those casts until nearly twenty-four months had gone by. Which meant that for the first two years of my life, I could neither walk, stand, nor even crawl. Weighted down by twin casts, like the “cement shoes” of Mafia lore, I could do nothing but sit.

What a nightmare, right? Poor kid couldn’t do anything, right?

Oh, but I could.

I could watch, listen, and think.

Any parent in that position would have been sorely tempted to overcompensate by plying me with dozens of toys to entertain me. My mother, in her endless wisdom, chose instead to give me one toy at a time. She’d leave me, say, with a single clothespin, and I would sit and play with that thing for what seemed like an eternity.

Not being able to crawl was a grievous limitation, no question. But here’s the thing: every limitation — every narrowing of focus, every closing of a multitude of doorways — offers its own path of lasering clarity.

Today, I write parables. The Go-Giver. The Latte Factor. Out of the Maze. The Vagrant. And so on.

I’ve found that it’s easy to write a mediocre parable, but exceedingly difficult to write a good one. What makes it so hard is that most of the usual narrative tools are withheld.

In a novel, or an essay, or a memoir, or a how-to or business guide or nearly any other type of book, you can elaborate on any given point at length if you feel like it. A novelist can tell you all about the hero’s appearance, about what they’re thinking, about their childhood and family history, their greatest fears and deepest yearnings.

Not in a parable. Take Joe, in The Go-Giver. What color are his eyes? How short or tall is he? What’s his last name? Where does he live? Give up? You don’t know?

Neither do I.

That’s the challenge of a parable: you don’t have the freedom to say a lot. You have to figure out how to say a lot with a little.

Sort of like sitting in a playpen for an hour with nothing but a clothespin.

“So, when you started writing novels, with those Chief Finn thrillers, I’ll bet that felt great, huh? All that freedom, all that opportunity to stretch out and write whatever you felt like writing?”

Not so fast. Because, as I soon learned in writing Steel Fear, thrillers have their own limitations. A thriller, like the great white shark, has to keep moving to get oxygen. If it stops, it dies.

When I proudly showed my completed first draft to a story consultant (herself a successful author of thrillers), she read it all the way through and then said, “I don’t think you’re quite getting how thrillers work.” And she was right.

For the thing to work, I had to delete long passages of terrific prose, excise whole chapters, even eliminate entire characters. I ended up slicing out and discarding some 40 percent of what I’d written.

For the thing to work, I needed to sit in a playpen and rewrite that draft with nothing but a clothespin.

For the thing to work, to borrow the phrase from Michel de Montaigne that opens this month’s letter, I needed to force my manuscript through a narrow tube.

Writing a good thriller is just as hard as writing a good parable. So is writing good poetry — which is what Montaigne was actually talking about with his “narrow tube” image. The full passage (it’s from Essay #26 of his Essays, Book 1) goes like this:

“Just as the trumpet’s voice rings out clearer and stronger for being forced through a narrow tube, so too a saying leaps forth much more vigorously when compressed into the rhythms of poetry.”

Parables, thrillers, poetry, memoirs, fantasies, business books, children’s books… every genre, every form of creative expression, has its own version of that narrow tube. Without it, if the writer just wrote whatever he or she felt like putting down on the page without the constraints of that form, the result would be a mess. Like trying to play the trumpet … without the trumpet.

It is those very constraints that enable the parable, the thriller, the poem, the children’s book, to find its way to greatness.

Limitations, as I learned in writing The Go-Giver and then again in writing Steel Fear, are not handicaps or barriers to opportunity. The limitation is the opportunity. The removal of possibilities is what forges the path to achievement.

The obstacle, as Ryan Holiday says in his excellent book of the same name, is the way.

I like the way the Tom Hanks character says it in that wonderful 1992 film A League of Their Own, speaking of pro baseball:

“It’s supposed to be hard. The hard is what makes it great.”

Of course, Montaigne was not writing only about how poetry works. He was also observing how human beings work. Because the secret to great art is also the secret to a great life.

When you’re young, anything is possible. But it turns out that isn’t as exciting as it sounds, because when the possibilities are endless, it’s surprisingly easy to be hobbled by a lazy sort of aimlessness. As the Cheshire Cat told Alice, if you don’t know where you’re going, then it doesn’t matter much which way you go.

It’s only when your field of choices narrows that your genuine creative energy starts being channeled into something powerful and meaningful.

Boil a gallon of water in an open vessel, and it simply evaporates. Enclose that boiling water in a tightly sealed chamber, allowing the steam to escape only through a single tiny opening, and now you can make an espresso or drive a hundred-ton locomotive.

Same boiling water. Same energy, same effort. The difference is the structure … which is to say, the stricture.

We human beings are big on freedom, and freedom is glorious, as far as it goes. But in the service of creating anything meaningful, anything great, it goes only so far. In fact, I would go so far as to say that freedom isn’t truly, fully freedom until it encounters constraints.

For freedom to express itself, it needs a good narrow tube.

Limitation = liberation.

So my question for you:

What limitations on your life have helped your voice ring out clearer and stronger? (If you trust me enough to share this, REPLY HERE — I would love to read your answer!)

One more example before I leave you: marriage.

A strong relationship is a narrow tube. When you live alone, you can do whatever you want, eat whatever and whenever you like, leave whatever mess you please.

A full-time, long-term relationship changes all that. It limits your choices; it constrains you. But here is the irony of it, and the beauty of it: it is that very set of constraints that opens you up to the possibility of becoming your greatest self.

This is the secret the wise old Jeremiah Janelle imparts to Tom in The Go-Giver Marriage:

“The purpose of marriage is to give yourself fully to another — and in the process, become your best self.”

My March wish for you:

That you take a little time every day to contemplate the greatest constraints of your life — and the ways they have allowed you to become a greater version of yourself.

About the writer

On February 28, 1571, a moderately wealthy French nobleman, lawyer and diplomat named Michel de Montaigne gave himself a thirty-eighth birthday present: he moved a chair, a table, and a library of roughly a thousand books into the tower of his family castle in Bordeaux, shut the door, and began to write.

He wrote about anything and everything, constantly interrupting his own topics with personal anecdotes, observations, and ruminations, resulting in a style that to his contemporaries seemed self-indulgent and confusing but was soon recognized as ground-breaking.

Born in 1533, young Michel was certainly forced through a narrow tube in his upbringing. As an infant he was placed with a peasant family, in whose tiny cottage he spent his first three years of life, the purpose being, according to his father, “to draw the boy closer to the people.”

Once back in the family’s château, the boy was allowed to speak only Latin for another three years, and was attended to by servants under strict orders to speak and respond only to Latin. Greek was soon added to his regimen, so the boy could be properly schooled in the classics. (Plutarch and Lucretius were among his favorites.) His father had a musician awaken him every morning, playing a different musical instrument, to further his education.

As a young adult, Michel entered into a career as a lawyer. His gifts as a counselor, confidant, and diplomat soon won him an appointment to the court of Charles IX.

By his thirty-eighth year, having accumulated a rich résumé of diplomatic accomplishments, he retired to his family estate and began to write what would become his most famous life’s work.

Montaigne published his massive volume of writings under the title Essais. It is no exaggeration to say that in these rambling, rhapsodic excursions, the man singlehandedly invented the modern essay.

The word “essay” means “attempt,” and Michel’s stated plan was to attempt to describe the experience of being human, especially through the lens of his own humanity, with complete frankness. As Montaigne himself wrote in his essay “On Vanity”:

“Anyone can see that I have set out on a road along which I shall travel without toil and without ceasing as long as the world has ink and paper.”

He wrote about everything — and judged almost nothing. His motto, “Que sais-je?” meaning “What do I know?” (the implicit shrug suggesting his answer: “Not much”), exemplified his distrust of the very idea of absolute certainty, also reflected in his disgust with the religious conflicts of his age.

One of his favorite philosophers, the third-century skeptic Sextus Empiricus, famously cautioned his followers to “suspend judgment” on everything but the experience of their own senses.

Montaigne was a complicated man; in his own words:

“bashful, insolent; chaste, lustful; prating, silent; laborious, delicate; ingenious, heavy; melancholic, pleasant; lying, true; knowing, ignorant; liberal, covetous, and prodigal.”

And his readers were captivated. Montaigne published his first two volumes of Essais in 1580, and by the time he put out a third in 1588, pretty much everyone in France who could read had gobbled up the first two. In sixteenth-century terms, Michel had written a bestseller. As he confessed:

“The public favor has given me a little more confidence than I expected.”

His withdrawal to ivory-tower isolation was not permanent. In 1850 he left his castle for a year of traveling, which he adored, and then went on to serve several terms as mayor of Bordeaux, moderating between the warring Catholics and Protestants and working tirelessly behind the scenes to promote peace, dialogue, reasonable compromise, and national unity.

In his youth, Montaigne was terrified of death. His best friend, the poet Étienne de La Boétie, died at the age of 33; soon after that Michel’s father died of complications from kidney stones, and his younger brother succumbed to a fatal hemorrhage after being hit in the head by a tennis ball.

Ironically, it was a near-death experience resulting from a riding accident that persuaded young Montaigne that death was a natural occurrence, even a pleasant one, and not to be feared.

In fact, his regard for death was a major factor in his decision to retire and write, led by a sense that in writing he could find a kind of immortality that the flesh would not grant.

Montaigne once described conversation as “sweeter than any other action in life,” adding, “If I were forced to choose, I would rather lose my sight than my hearing and my voice.” Yet this, alas, was a choice he would not be granted.

At the age of 59 he contracted quinsy, a rare infection of the tonsils that paralyzed his tongue. Perhaps mercifully, he did not suffer this perverse state of muteness for long: death quickly claimed him.

Montaigne’s Essais had a profound influence on modern psychology, modern theories of education, philosophy, and especially on the art of writing itself. The English essayist William Hazlitt claimed that Montaigne “was the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man.”

It was Leonard Woolf (husband of Virginia) who dubbed him “the first completely modern man,” adding that his modernity lay in his “intense awareness of and passionate interest in the individuality of himself and of all other human beings.” The “first modern man” label has firmly stuck.

A roster of Montaigne’s ardent fans would include Sir Francis Bacon, William Shakespeare, John Webster, Lord Byron, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, Aldous Huxley, and Eric Hoffer, who declared, “He was writing about me. He knew my innermost thoughts.” Emerson made a similar observation on the experience of reading Montaigne:

“It seemed to me as if I had myself written the book, in some former life, so sincerely it spoke to my thought and experience.”

NOTE: I first bumped into this Montaigne quote in a recent issue of Ryan Holiday’s excellent newsletter The Daily Stoic, which I highly recommend.

Recommended Reading

If you’ve never read any Montaigne, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

Essays (first published 1580–1595), his lifelong exploration of what it means to be human.

The Complete Essays of Montaigne, edited by Donald Frame (1958), the standard modern edition.

How to Live: A Life of Montaigne by Sarah Bakewell (2010), a lively contemporary companion.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.