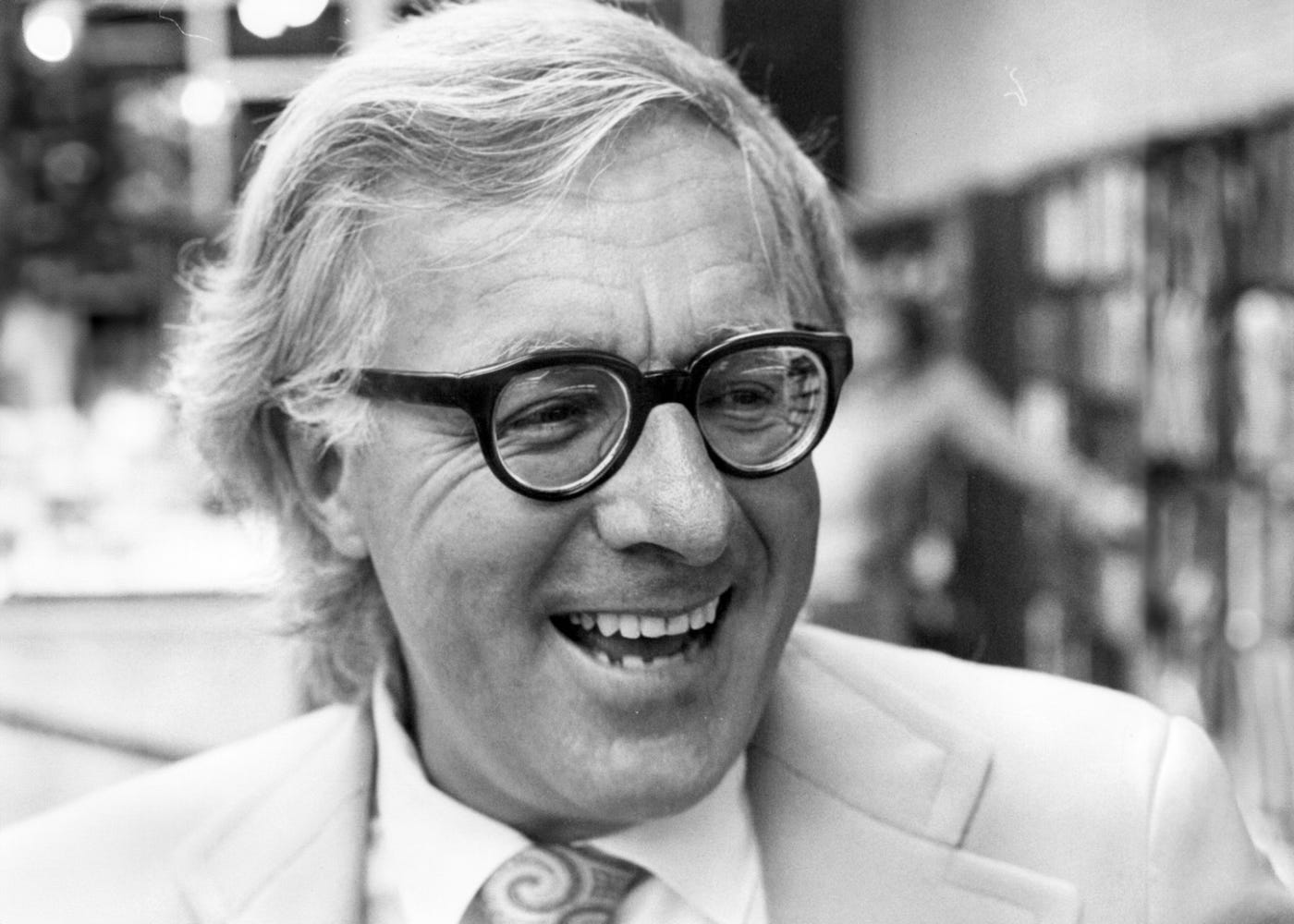

On feeling

RAY BRADBURY | “You must never think at the typewriter. You must feel.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

QUIZ: Five frogs sat on a lily pad. One decided to jump off. How many were left?

Before you answer, let me tell you about a recent situation with a few of the writers in my coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.

In our group, we’ve got people who are writing memoirs, how-tos, business books, novels, fantasies, and parables (i.e., books like The Go-Giver or The Latte Factor). We talk live twice a week via Zoom to check in, report our progress, get support when we’re stuck, cheer each other on, and so forth.

A few weeks ago I noticed that a number of these folks were getting mired down in their planning: outlining, conceiving, brainstorming, diligently working away at clarifying just what it was they wanted to write … and not really moving forward.

My advice mostly boiled down to this: “It’s time to let go of all that and write.”

Seems obvious, right? I mean, that’s the real key to getting your book written: Put your derrière in the chair and write … right?

Yet it needs to be said, again and again. Because we resist. And we resist because it’s hard.

There is a kind of safety in planning.

There is risk and danger in doing.

Writing is like skydiving: you can’t do it while remaining inside the plane. It’s Butch and Sundance leaping off the cliff — even though Sundance says he can’t swim and Butch says the fall will probably kill them. Because when you let go of the lifeline of your plan, of thinking about writing and talking about writing, you expose yourself to the freefall of uncertainty.

You become vulnerable.

For writers, sometimes it’s more Butch whispering in our brains:

The fall will probably kill me … What I write won’t be any good, it will suck, everyone will hate it, no one will read it.

And sometimes it’s more Sundance:

I don’t know how to do this! I don’t have the skill, I don’t have the talent, I don’t know what I’m talking about … I can’t swim!

For all of us humans (and not only writers) it’s often the same. Don’t know what we’re doing. The fall will probably kill us. Better to stay up there on the cliff. Better to remain inside the plane.

Sometimes I’ll be talking with my wife, Ana, about a personal situation I’m going through with one of my kids, or a friend, or a colleague, ruminating over thoughts about what I should or shouldn’t do about it, and she’ll say, “How does all this make you feel?” — and I resist answering, at first. Because I don’t know exactly how I feel.

Reluctantly, I step to the edge of the cliff and start into a reply, and the words come out awkward, clumsy, wrong.

But that doesn’t matter. That’s actually good. Because it’s the truth, or at least, it’s on the way to the truth.

Writing, most of the time, is just like that. It’s not clean, elegant, or accurate. It’s a mess. Far easier to take a step back onto the cliff, into the safe bosom of the plan, away from the terrifying empty page, and spend a little more time ruminating.

Fascinating word, ruminate. It traces back to rumen, the cow’s first stomach, the part that keeps tossing partially digested food back up to chew on a little more before actually swallowing. When you ruminate you are performing the human being’s version of chewing the cud.

And here’s what that wonderful writer Ray Bradbury has to say about that:

“I’ve had a sign over my desk for 25 years now which reads, DON’T THINK. You must never think at the typewriter. You must feel.

“The worst thing you do when you think is lie. You can make up reasons that are not true for the things that you did. And what you’re trying to do as a creative person is surprise yourself. Find out who you really are, and try not to lie. Try to tell the truth all the time.

“And the only way to do this is to be very active and very emotional and get it out of yourself, and making lists of things that you hate, and things that you love. You write about these, then, intensely. And when it’s over, then you can think about it. Then you can say, well, it works or it doesn’t work. Something’s missing here. And then if something is missing, you go back and re-emotionalize that, so it’s all of a piece.

“But thinking is to be a corrective in our life. It’s not supposed to be the center of our life.

“Living is supposed to be the center of our life.”

And no, this isn’t only about writing. To paraphrase Bradbury:

You must never think —

when you write…

when you talk with a friend…

when you make a sales call…

when you stand up to speak before a group…

when you sit down to comfort a hurting child…

when you perform on a musical instrument…

when you cook a meal…

— you must feel.

And yes, you will have prepared. You will have thought through some of the key points you want to make before you stand up to speak, learned the notes of your piece of music before you play, gathered an idea of what dish you’re making and what ingredients you have at hand before you cook. You’ll do some thinking ahead of time, and you’ll do some thinking afterward, too.

But when it’s time to speak? to make the call? to cook the meal? to comfort the child? to write? You enter a world that cannot be navigated by thought, but only by feeling.

So my question for you:

In what areas of your life do you perhaps need to think less and feel more; to ruminate less and leap off more cliffs? (If you trust me enough to share this, REPLY HERE — I would love to read your answer!)

Which brings me back to the writers in my coaching group, and what I call “the secret to writing a good parable.” It’s a three-step process. Here’s how it works.

Step 1. You get your big idea, that set of Key Concepts you want to convey (your Three Laws of this or Ten Rules of that) about leadership, or resilience, or success, or happiness, or financial wisdom, or fulfilling relationships, or whatever your topic is.

Step 2. You come up with a main character, the seeker to whom your reader will relate, and you place them in a situation, probably some sort of challenge, problem, or crisis, the solving of which is somehow going to illustrate your Key Concepts — exactly how, you probably don’t know yet, but it’s a place to start.

Okay, now, ready for Step 3? Here it is:

Forget about your Key Concepts.

Toss them out the window. Purge them from your thoughts. Forget ’em. And write.

Because your parable isn’t really about your Big Idea. It’s about the reader and their human experience, and therefore it’s about your main character and their human experience. It’s not about the ideas. It’s about the story. And a story isn’t something you think, it’s something you feel.

Throw away the Big Idea and step into the shoes of your character. Enter their world, put yourself in their situation, and see what happens. Trust that your Big Idea will find its way in, and just let the story play out.

Live it. Be awkward, clumsy, wrong. You can fix it later, improve it, rewrite it, perfect it. But not now.

Right now, no thinking, just feel your way through. Let the mess commence.

And come to think of it, perhaps that is not only the secret to writing a good parable.

Perhaps it is also the secret to living one.

Now, about those five frogs…

Of the original five frogs, how many are left?

Answer: five. They’re all still sitting there on that lily pad, all five of them. That one only decided to jump off. It hasn’t actually done it yet.

My May wish for you:

That you take time every day to find a meaningful cliff in your life, large or small — and then jump off and swim.

About the writer

Let me tell you about Ray Bradbury.

This playful, affable second son of an electrician from a small Midwestern American city grew up to become one of the most popular, influential, and beloved science fiction writers of the twentieth century.

More than that, he was one of the most popular, influential, and beloved writers, period, of the twentieth century.

Bradbury loved the movies, loved to draw, loved performing magic tricks, loved America, and most of all, he loved to write. Author of such classics as The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, Dandelion Wine,Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Fahrenheit 451, he penned over two dozen enduring novels and story collections containing over 600 short stories, as well as screenplays and teleplays, comic books, collections of poetry, essays, and more.

There were a few things Bradbury hated, too.

He hated intolerance, authoritarianism, and oppression in all its guises. He was repelled by any hint of pretention, deeply distrustful of all government and most education beyond kindergarten.

And technology? That he both loved and loathed.

His stories were astonishingly prescient, painting vivid pictures of Bluetooth earbuds (“ear thimbles”) in 1953 (Fahrenheit 451), artificial intelligence in 1962 (I Sing the Body Electric), and a terrifying version of virtual reality in 1950 (The Veldt).

Yet the man who spent seventy years showing us the future never used a computer (“I already have a typewriter,” he said, “why would I need another one?”) and never drove a car (never even got a drivers license). The writer who took generations of us to Mars refused to fly on airplanes.

And speaking of the future, Bradbury is also the essayist who famously wrote”

“People want me to predict the future, when all I want to do is prevent it.”

Raymond Douglas Bradbury was born in 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, son of a lineman for the local power company who went broke and eventually relocated his family to Southern California.

At the age of three Ray saw his first film, the just-released Hunchback of Notre Dame with Lon Chaney, and adored it. Two years later he dragged his mom back to the theater for Chaney’s next film, The Phantom of the Opera, and it was all over: he was in love with movies for the rest of his life.

When he was four, his parents taught him how to read newspaper comics. His aunt read him Frank Baum’s Oz books. When the Buck Rogers comic strip appeared in 1929, the boy would spend his days “in a state of near hysteria waiting for the comic to slap onto my front porch each night in the evening paper.”

As a teenager, after their move to Los Angeles, Ray would criss-cross Hollywood on roller skates, collecting autographs and taking photos with such stars as Jean Harlow, Marlene Dietrich, and George Burns. Katherine Hepburn once drove him around Beverly Hills; Doris Day used to wave to him every day as she rode by on her bike.

A turning point came one autumn day during the Bradbury family’s final year in Illinois, when Ray went with his dad to a local carnival that had just blown into town. A performer who went by the name of “Mr. Electrico” sat in what looked like an electric chair, a stagehand pulled a switch, and Mr. Electrico was charged with 50,000 volts of pure electricity (so the promotion said).

As Bradbury later recalled:

“Lightning flashed in his eyes and his hair stood on end.”

The next day he went back on his own, introduced himself to the man, and they talked. He stayed to see the act again, and this time as Electrico sat in his electrified chair, all lightning eyes and dancing hair, he reached out with a static-charged sword and tapped 12-year-old Ray on the brow, nose, and chin, like royalty knighting a champion.

“Live forever,” he whispered.

Right then and there, Ray decided it was his path in this life to write, and write, and write.

In high school he established an unswerving routine of turning out at least a thousand words a day on his typewriter. His first major success came at the age of 27, when a young editor at Mademoiselle named Truman Capote noticed one of Ray’s short stories from a pile of unsolicited manuscripts and tapped it for publication.

Homecoming, the tale of a boy who feels like an outsider at a family reunion of witches, vampires, and werewolves because he lacks supernatural powers, won an O. Henry Award — the oldest and one of the most respected American prizes for literature — as one of the most exceptional American short stories of the year.

A frenzy of writing followed, and with it a readership and reputation that soared like a rocket ship reaching for the stars.

More than 8 million copies of his books have sold in 36 languages. He wrote the screenplay for the revered John Huston/Gregory Peck film version of Moby-Dick, hosted a mid-1980s TV show called Ray Bradbury Theater, wrote for The Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents, worked in architecture, was a celebrated visual artist and decent stage magician.

During his long career he was awarded a National Medal of the Arts, every conceivable science fiction award, an Emmy, an Academy Award nomination, a handful of honorary doctorates, and a special citation from the Pulitzer Prize jury for “for his distinguished, prolific, and deeply influential career as an unmatched author of science fiction and fantasy.”

Among those who have claimed Bradbury as among their greatest heroes and muses are Steven Spielberg, Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, Junot Diaz, Michael Chabon, Colson Whitehead … the full list is probably infinite.

Even from his earliest years Bradbury sought to bring science fiction — in those days still looked down on as fringe pulp stuff, rife with gadgetry, gizmos, rayguns, and no real substance — to a wider audience. He stripped out the sciency jargon and wrote about real people in believable settings (often small-town, Norman Rockwellesque places that echoed his Waukegan childhood), speaking in plain, folksy language.

He wasn’t writing escapist fantasy: he was producing biting social commentary.

As Bradbury himself put it in a 2010 interview in The Paris Review [note: all the excerpted passages that follow are drawn from this remarkable interview], his point was to write metaphors.

“Every one of my stories is a metaphor you can remember. The great religions are all metaphor. We appreciate things like Daniel and the lion’s den, and the Tower of Babel. People remember these metaphors because they are so vivid you can’t get free of them and that’s what kids like in school. They read about rocket ships and encounters in space, tales of dinosaurs.”

He would frequently cite the Greek myth of Perseus as a metaphor for science fiction. Perseus was the hero who took on the challenge of killing Medusa, the terrifying Gorgon whose face would instantly turn anyone who gazed at it to stone.

Perseus’s solution was to approach Medusa while looking over his shoulder at her reflection in the polished surface of his bronze shield, which allowed him to take perfect aim as he swung his sword and cut off her head.

“Instead of looking into the face of truth [said Bradbury], you look over your shoulder into the bronze surface of a reflecting shield.”

Science fiction may fix its gaze on some fictional future — but in that reflection it’s really taking aim at what is happening right here in our very real present. As he told The Paris Review:

“Take Fahrenheit 451. You’re dealing with book burning, a very serious subject. You’ve got to be careful you don’t start lecturing people. So you put your story a few years into the future and you invent a fireman who has been burning books instead of putting out fires—which is a grand idea in itself—and you start him on the adventure of discovering that maybe books shouldn’t be burned. He reads his first book. He falls in love. And then you send him out into the world to change his life. It’s a great suspense story, and locked into it is this great truth you want to tell, without pontificating.”

His writing could also be intensely lyrical, evidence of his lifelong passion for poetry:

“My favorite writers have been those who’ve said things well. I used to study Eudora Welty. She has the remarkable ability to give you atmosphere, character, and motion in a single line. In one line! … Welty would have a woman simply come into a room and look around. In one sweep she gave you the feel of the room, the sense of the woman’s character, and the action itself. All in twenty words. And you say, How’d she do that? What adjective? What verb? What noun? How did she select them and put them together? Sometimes I’d retype whole sections of other people’s novels just to see how it felt coming out, learn their rhythm.”

For all his social critique, Bradbury was a perpetual optimist. Speaking of fellow science fiction writer Kurt Vonnegut, Bradbury said, “He had problems, terrible problems. He couldn’t see the world the way I see it. I suppose I’m too much Pollyanna, he was too much Cassandra.”

Although one thing he and Vonnegut certainly shared was how devoted they both were to their wives, whom both described as their best friends, and both of whom became the still points around which the writers’ worlds revolved.

One April day when he was 25 years old, Ray was browsing a downtown LA bookstore, when he had that unshakeable feeling of being watched. Looking around, he noticed that the clerk’s eyes were following him around the store. Why? Because the young man was browsing with such focused intensity, she thought he was about to steal something.

Her named was Marguerite McClure, but her friends all called her Maggie. They talked; he told her he was a writer; they went out for coffee.

Her friends warned her not to get involved. He was clearly going nowhere, they told her. When she repeated these warnings to him, he replied, “I’m going to the moon, and I’m going to Mars. Do you want to come along?” She said, “Yes.”

A year later they were married, and they stayed together happily for the next five and a half decades until her death. She was the only woman he ever dated.

Asked about the secret to their happiness, Bradbury said:

“If you don’t have a sense of humor, you don’t have a marriage. In that film Love Story there’s a line, ‘Love means never having to say you’re sorry.’ That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard. Love means saying you’re sorry every day for some little thing or other. You know? So being able to accept responsibility, but above all having a sense of humor, so that anything that happens can have its amusing side.”

In many ways, Bradbury was perpetually that little boy, Jonesing for his Buck Rogers and mesmerized by Mr. Electrico, who never grew up — to the endless benefit of humanity.

His grandchildren remember him as having more toys than they did. His home office was cluttered with toy ray guns, robots, stuffed dinosaurs, an oversized stuffed Rocky and Bullwinkle lounging in cushioned chairs, and even a head floating in a glass jar, courtesy of Alfred Hitchcock. Every Christmas, at Ray’s request, Maggie would give him toys rather than any more “useful” gifts.

In 1999 he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed, wheelchair-bound, and unable to write on his own. Still, he continued on. A few days after his stroke he called his daughter Alexandra, then working for him as his assistant, from his hospital bed, and asked her to come over.

“I told her to bring the manuscript I was working on, my mystery novel Let’s All Kill Constance. I dictated the story to her and she typed it up. And that’s the way I have written since. I call her on the phone, dictate my stories to her, and she types them up and faxes them to me. Then I edit with a pen. It’s not an ideal process, but what the hell.”

He continued making public appearances for another decade until his “retirement” in 2009. But he continued writing still. In the spring of 2012 he contributed an essay to a special “science fiction” double issue of The New Yorker on what inspired him as a boy.

It would be his last written work, published a week before his death at the age of 91.

His mortal passing notwithstanding, as millions of devoted fans from a dozen generations will attest, Mr. Electrico had it right: Ray Bradbury lives forever.

Recommended Reading

If you’ve never read any Bradbury, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

Fahrenheit 451 (1953), his celebrated dystopian novel.

The Martian Chronicles (1950), poetic tales of space and humanity.

Dandelion Wine (1957), his nostalgic ode to summer and memory.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.