On eternity

MARY OLIVER | “Something is wrong, I know it, if I don’t keep my attention on eternity.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

When I go to bed at night, I have a habit: I lie down on my right side and watch Ana as she settles in. She puts everything in order on her bedside table, shuts off her light, arranges her pillows just so, organizes her covers, turns onto her left side, looks at me … and smiles.

When our smiles meet, the years fall away and I see the 11-year-old Ana, the 6-year-old Ana, the 90-year-old Ana, and and they’re all the same. The eternal Ana.

It’s one of my favorite moments of the day.

— Early morning, settling into my Marty Crane chair with blank pad and pen to work on some piece of writing, I slip on my headset and start playing Bach’s The Art of Fugue, or Philip Glass’s soundtrack to The Hours, or a favorite soundscape of a bubbling brook, and the music pulls me out of my chair and through the walls and into outer space …

— Another: I take our dog Phin out for a pee first thing when he wakes up, and he does something I love. No matter how urgently he has to go, when he gets outside onto the grass he stops still, looks up our driveway toward the street, nose to the air, and stands there, feeling the air on his face. By the quivering of the skin around his snout I know he is taking in entire encyclopedias of scent, smells I’ll never in a million years be able to detect. His ears twitch at the tiniest sounds stirring in the far background. I know what he’s doing. He is loving life. I think he could stand there for an hour. I know I could. And then I give the leash a gentle tug, and he goes, Oh, right, and he pees, and we go back inside, and the day begins.

— And another: Reading some especially evocative passage of writing, I tumble into it headlong, the sheer language of it magically opening up intimate worlds of alien experience … Chris Pavone, Adrian McKinty, Tana French, Erik Larson, these alchemists of imagery and sound. Here is a passage (as yet unpublished) from Nizam Meah, a writer in my Writing Mastery coaching program, from his memoir about growing up in war-torn Bangladesh:

With no electricity to soften the night, the village was swallowed whole by darkness as soon as the sun slipped beneath the horizon. An impenetrable silence settled over the fields and homesteads, broken only by the distant strains of bhajans and the rhythmic drumbeats of Hindu chants drifting through the faint ether, or the melodic call of the muezzin echoing from a far-off mosque. My older cousins lighted kerosene lamps and chirags, their flickering flames casting trembling shadows on mud walls. But as the night deepened, even these small islands of light surrendered to the hush. The silence became absolute, pierced only by the wild sounds of nature: the screech of an owl, the mournful howl of a fox, the frantic barking of dogs in pursuit, or the stealthy prowl of a Bengal fishing cat, perceived by humans only by its haunting meow.

And another from Mollie Marti, another author in the program, writing in her parable about a soldier retiring from two decades in the service, cloaked in post-traumatic stress:

The corridor outside was quieter than he remembered it ever being. No one waiting. No ceremony. No sendoff. Just Daniel Rogan. Carrying a manila folder, a duffel bag, and a silence that somehow felt heavier than all the body armor he’d ever worn.

These magicians of words, those I know and work with and those I read and admire from afar, pull me out of my fabric of space-time and transport me to a dozen other dimensions and realities, tapping me into something universal and eternal.

Which brings us, naturally, to Mary Oliver.

The quotation at the top of this month’s letter is from “Upstream,” her first essay from a collection of the same name.

Oliver is a master, one of the greatest that ever lived, of capturing eternity in words. In this little gem of an essay she records her thoughts, impressions, and reflections as she traipses up a country stream on a spring day. Amid her trademark descriptions of nature, she keeps falling through the moment into something timeless. For example:

“I walk, all day, across the heaven-verging field.”

“The water pushed against my effort, then its glassy permission to step ahead touched my ankles. The sense of going toward the source. / I do not think that I ever, in fact, returned home.”

“Do you think there is anything not attached by its unbreakable cord to everything else?”

She then chronicles the march of adulthood and involvement in the things of the world

“With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats”

and how the tyranny of time begins to shackle us

“The clock! That twelve-figured moon skull, that white spider belly! … Every day, twelve little bins in which to sort disorderly life, and even more disorderly thought”

and how nevertheless, eternity keeps poking through:

“There is within each of us something that is not a child, nor a servant of the hours. It is a third self, occasional in some of us, tyrant in others. This self is out of love with the ordinary; it is out of love with time. It has a hunger for eternity.”

I’m not saying, and don’t think Oliver is either, that being time-bound is a bad thing. Time is where we live. It is our playground, the stuff that makes up our heartbeat, the tides of brain waves and rhythms of respiration. It is time (not love) that makes the world go round (love is what holds us together and keeps us from flying off into space).

But it’s so easy to become a prisoner of time.

Deadlines. Checklists. Errands. The tyranny of to-do’s, the haunting of the still undone. Alerts from the phone. The infernal screams of the social media beast, demanding our unconditional surrender.

One of the transcendent things about the great musicians, from Bach to Coltrane, is how they set up a time-container of meter, beat, and harmonic frame, and then brazenly escape it, like Houdinis of sound.

Architects do that too. In the pages of Blind Fear, Chief Finn stands in a cathedral in Humacao, Puerto Rico, recalling a time when Tómas, a Puerto Rican SEAL buddy, showed Finn and a few others around. One of the other SEALs looks up at the cathedral’s soaring marble ceiling and says, “How come they always built these old cathedrals with all that freakin’ wasted empty space up top?” And Tómas replies, “To leave room for God, moron.”

Cathedral = fixed structure + portal to eternity

My Marty Crane chair is a kind of cathedral. So is Mary Oliver’s country stream. So is lying on my side and waiting for Ana’s smile.

So my question for you:

What are your cathedrals? What are the moments of your life when time disappears and you touch eternity? (If you trust me enough to share this, REPLY HERE — I would love to read your answer!)

Eckart Tolle writes that we are powerfully drawn to flowers, puppies, kittens, lambs, and human infants because they are “messengers from another realm,” recent arrivals still damp with the fresh dew of timelessness.

We are not flowers or puppies, you and I, nor infants anymore. Yet as Oliver writes, there is within each of us something that is not a child, nor a servant of the hours … a third self, out of love with the ordinary, out of love with time.

A self that remembers.

We are all, I think, living our version of the Greek myth of Antaeus, a son of Gaia, goddess of the earth.

Antaeus was an unbeatable wrestler with a simple secret: as long as his feet touched the earth — his mother — he could not be conquered. It was Herakles who figured this out and defeated Antaeus by lifting him off the ground as he choked him, severing his connection with his source and rendering him helpless.

Tradition looks at Antaeus as the villain, Herkales the hero — but turn the story around and it becomes a cautionary tale.

Lose connection with your source, and you lose your capacity to endure.

My August wish for you:

That you take a little time every day to untime — to do whatever it is you need to do, go wherever you need to go, put yourself in whatever space you need to fall out of time and reconnect with immortality.

About the writer

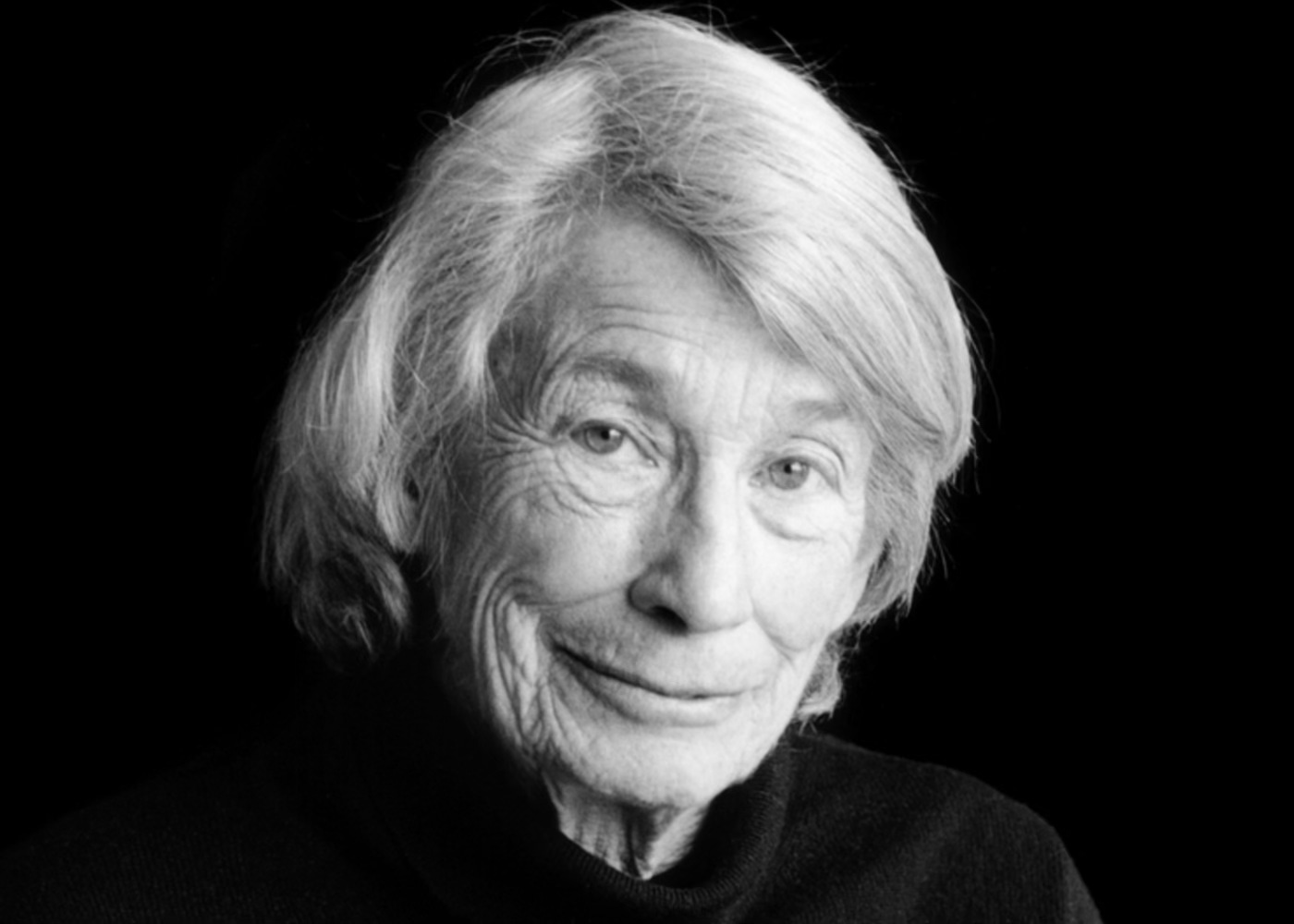

Mary Oliver is a study in contradictions.

Her writing was famous, even legendary, for its clarity and accessibility. Yet it could also be oddly polarizing. For example:

One of the most beloved and widely read poets of the twentieth century, she was also maligned and dismissed throughout her career by critics who derided her work as simplistic and without depth.

Her work earned her a Pulitzer, a National Book Award, a Guggenheim, a PEN New England, a Shelly Memorial Award, and five honorary doctorates; in 2007 the New York Times declared her “far and away, this country’s best-selling poet” — and yet the Times itself never once published a full-length review of any of her dozens of books.

Some feminists rejected her work, claiming it perpetuated stereotypes about woman and nature. Others applauded her celebration of female sexuality and and saw her work as empowering.

Her writing is personal, immediate, even intimate — yet she was a fiercely private person who rarely gave interviews, insisting the work speak for itself.

And that work speaks in two voices. Unabashedly devotional, her poems could at times read like prayers or sermons. On the other hand, as her obituary in the Times described it, “beneath her work’s seemingly unruffled surface [lay] a dark, brooding undertow.”

A review of her 1986 collection Dream Work described her writing this way:

“[Oliver is] among the few American poets who can describe and transmit ecstasy, while retaining a practical awareness of the world as one of predators and prey.”

Those two voices, what another observer called “the push and pull of the sinister and the sublime,” can be traced to her childhood.

Born in 1935 in a small town on the outskirts of Cleveland, Mary Jane Oliver grew up in a house she describes as “dark and broken … I had a very dysfunctional family, and a very hard childhood.”

In the essay “Staying Alive” from Blue Pastures (1995), she recalls a day when her father took her ice-skating, then forgot about her and went home alone, returning to fetch her only after a kind local took her in and called her home on the phone. Her father was all smiles and gracious warmth when he picked her up, and then:

“Then I put on my coat, and we got into the car, and he sat back in the awful prison of himself, the old veils covered his eyes, and he did not say another word.”

Ruled by a sexually abusive father and passive, neglectful mother, Oliver’s home life became something to flee, and she found that escape in two places: nature, and words.

“The natural world, and the world of writing … these were the gates through which I vanished from a difficult place.”

She spent much of her childhood taking long solitary walks in the forests and undeveloped countryside of rural Ohio. (“The only record I broke in school was truancy.”)

In her description of that spring trek that opens Upstream, Oliver casually mentions that she was walking not only upstream but also away from her parents, hinting that she got so lost the authorities had to be called in. (“Finally I was advertised on the hotline of help, and yet there I was, slopping along happily in the stream’s coolness.”)

She began writing poetry at age 13, doing most of her writing on those walks in the woods, jotting down inspirations as they came. (She once hid pencils among the trees so she would never be caught unprepared.)

The day she graduated high school she left home, never to return.

A spur-of-the-moment road trip to the upstate home of the recently deceased Edna St. Vincent Millay, one of her literary heroes, turned into a six-year stay helping Millay’s sister Norma organize the late poet’s papers.

Over those and the following few years, Oliver met her true love and lifelong companion, a photographer by the lyrical name of Molly Malone Cook; published her first collection of poems (No Voyage, and Other Poems); and found both a home and a muse in Provincetown, the famously writer-friendly enclave at the tip of Cape Cod, where she would spend most of the rest of her life.

“[I] fell in love with the town, that marvelous convergence of land and water; Mediterranean light; fishermen who made their living by hard and difficult work from frighteningly small boats; and, both residents and sometime visitors, the many artists and writers.”

The local landmarks are featured so vividly in Oliver’s writing that a Times travel writer once assembled a guided tour of Provincetown using only Oliver’s poems.

Almost from the start, Oliver’s poetry attracted legions of devoted followers. Her word paintings of nature often brought comparisons to Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, the intimacy of her voice to Emily Dickinson, and its naturalistic, almost mystical quality of spiritual musings to Emerson, Thoreau, and Blake.

Her writing is best known for its lyrical observations of the natural world (many of her poems bear titles like “Mushrooms,” “Egrets,” “The Waterfall,” The Rabbit,” and perhaps her most famous poem of all, “Wild Geese”).

Yet at its core, her real exploration is into just what the hell we humans are supposed to make of our own place within this natural cosmos.

Here is the conclusion of “The Summer Day,” perhaps her most famous poem:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

Or as she put it in Upstream:

“May I be the tiniest nail in the house of the universe, tiny but useful.”

In 2012, at the age of 77, Oliver, a lifelong smoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer, and the experience inspired a four-part poem (for Oliver, an epic) entitled “The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac,” published in the 2014 collection Blue Horses.

Why should I have been surprised?

Hunters walk the forest

without a sound.

The hunter, strapped to his rifle,

the fox on his feet of silk,

the serpent on his empire of muscles —

all move in a stillness,

hungry, careful, intent.

Just as the cancer

entered the forest of my body,

without a sound.You could live a hundred years, it’s happened.

Or not.

I am speaking from the fortunate platform

of many years,

none of which, I think, I ever wasted.

Do you need a prod?

Do you need a little darkness to get you going?

Let me be urgent as a knife, then,

and remind you of Keats,

so single of purpose and thinking, for a while,

he had a lifetime.

(The poet John Keats, it should be noted, died at 25.)

Her cancer “was treated” (we are not told how), and she was given a clean bill of health. Nevertheless, as she put it in a 2015 interview, “It feels that death has left his calling card.” She died of lymphoma in early 2019 at the age of 83.

In one of her best-known poems, “When Death Comes” (1991), she wrote:

When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

No need to wonder, Ms. Oliver; you did far more than simply visit — you inhabited the world in all its wondrous fearsome beauty, and left wide open the doors to the cathedral, so we could enter in and inhabit it with you.

Recommended Reading

If you’ve never read any Oliver, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

Devotions (2017), her handpicked lifetime selection of poems.

American Primitive (1983), the Pulitzer Prize winner that made her name.

Upstream (2016), her luminous essays on creativity and the natural world.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.