On being a hero

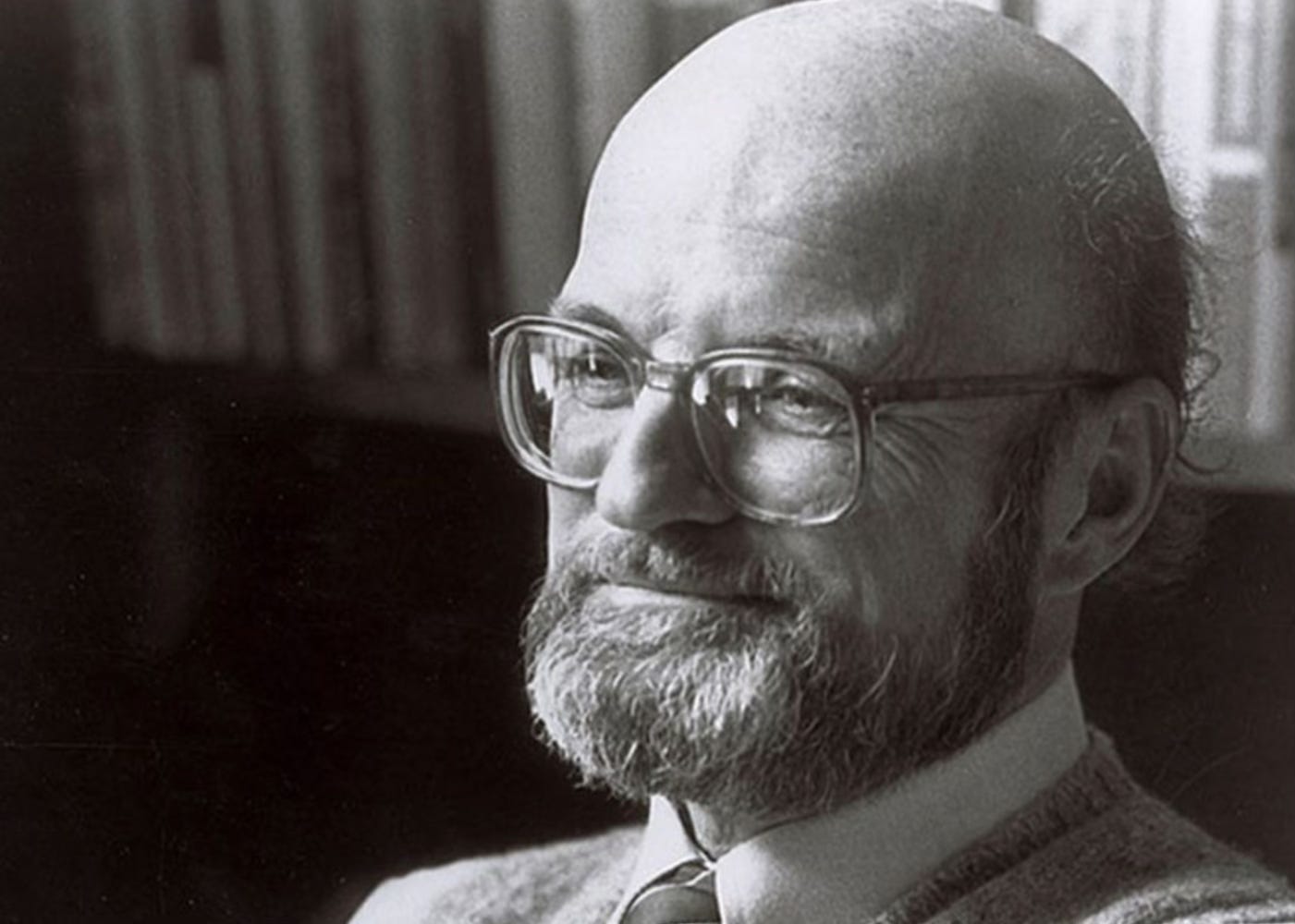

JOHN BARTH | “Everyone is necessarily the hero of his own life story.”

Dear Faithful Reader,

When I was 8, I wanted to be Batman.

That summer my parents and I had spent a month in Italy. At the time, I was wrapped up in fantasies of being Fireboy, a superhero I’d invented who wore tights and a red tee shirt with a big “F” emblem on the chest (I’d conscripted my mom to do the sewing). I brought the costume with me to Italy and wore it every chance I got, to the hearty amusement of our Italian hosts, who called me “Fra Diavolo.”

This, I learned, was Italian for “brother devil.” It was also the nickname of a hot-headed 18th-century Italian revolutionary (as well as a spicy pasta sauce), but I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that they weren’t understanding that I was Fireboy, a boy who could fly, see through things, and burn down buildings with his fiery vision.

This frustrated me terribly, but I lacked the language skills to explain who I really was.

Back in the States, I soon moved on from Fireboy and other Superman-inspired characters to fasten my focus on the Caped Crusader of Gotham City.

Batman was more interesting. He was human, and his superpowers were more believable. Best of all, he deployed all sorts of extremely cool gadgets and devices. I thought it would be amazing to be Batman, on a mission to set things right and make Gotham a better place.

I continued to fixate on Batman and a host of other DC superheroes until one winter morning, when my mother, sitting by the fireplace in our living room, looked up and saw 9-year-old me trudging down the stairs with a stack of comic books in my arms.

Without a word, I walked to the fireplace, dumped them all in, and watched them burn.

She asked me why I was doing this. I was too choked up to answer, and even if I could, I wouldn’t have known what to say. I didn’t understand it myself, not then.

I’d just finished reading The Last Battle, the final volume of C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. The book left me shattered, thunderstruck by the idea that there was a vast reality beyond that of our mundane senses. A world that was bigger on the inside than it was on the outside; a world that lay “further up and further in.”

Lewis possessed a whole other level of X-ray vision.

That long-gone stack of first-edition DC comics would probably be worth a bundle today, but what I gained in incinerating them was priceless: it ushered me into a new chapter in the hunt for my own life story.

In the years since there’ve been plenty of turns and surprises, twists in the plot; career changes and catastrophes, triumphs and trials. People I thought were major characters who quickly faded from the narrative, minor characters who turned out to play central roles. Allies who proved not to be so after all, mentors who arose from unexpected quarters.

Today I’m still on a mission to make the world a better place, though without cape or cowl, and the gadgets and devices I deploy these days are verbs and nouns, images and metaphors, rhythm and cadence. My first website, in 2007, bore this inscription:

“Jedi Knights roam the universe, helping to set things right. What I do is something like that—the difference being, I help set things write.”

Aren’t we all looking for pathways to use our superpowers to help set things right?

My father fled the Nazi hijacking of his homeland, bringing his music (his superpower) with him, and spent the rest of his life conducting Bach in America.

My wife Ana’s superpowers are empathy and research: she feels others’ feelings more deeply, and understands more about the machinery of emotional, mental, and biochemical health, than anyone else I’ve ever known, and she wields those powers in her coaching and therapy sessions.

Making the world a better place.

My father and my wife are both heroes of mine. I have other heroes, too, and so do you. We all have our heroes. But I have a theory about heroes:

We choose the heroes we admire not simply for who they are, but for the hero they point to in ourselves.

Because, as the American novelist John Barth put it in that immortal line: “Everyone is necessarily the hero of his own life story.”

To the ancient Greeks, who coined the term, a “hero” was a person of both mortal and divine origins, half-man and half-god, personal and eternal, idiosyncratic and universal.

I believe that describes every one of us. Each of us is a hero, or has a hero self, that part of us that touches what is universal and eternal. It is that part in us that yearns to live in undying pursuit of a quest, and in that undying, achieves immortality.

So my question for you:

What is that quest that animates your life story? (If you trust me enough to share this, REPLY HERE — I would love to read your answer!)

If each of us is the hero of our own story, the burning question then becomes, just what exactly is that story?

Inigo Montoya, in The Princess Bride, was never in doubt: his story was that of the avenging son. (“My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”) That is, until Count Rugen lay dead at his feet, and suddenly Montoya was lost. “I don’t know what to do with the rest of my life,” he confessed.

Fortunately he had Westley, who pointed out that he would make a great Dread Pirate Roberts.

Not all of us have Westley standing by, so we need to figure it out ourselves.

And that may be the most important job we’ll ever have. Because the greatest tragedy, I think, is going from cradle to grave without ever quite finding the story we’re meant to be living.

This is what happens in the 1993 film Falling Down. Michael Douglas plays Bill Foster, a divorced and recently unemployed defense engineer who gets stuck in LA freeway traffic on his way to his ex-wife’s house for his daughter’s birthday.

Foster’s frustration — with the traffic jam, with the direction his life has taken, with the whole world — boils over into an urban rampage that leads to violence and mayhem and ends with a fatal confrontation with a cop, which is when it finally sinks in just how far off the rails he’s gone.

“I’m the bad guy?” he says, bewildered. “How’d that happen? I did everything they told me to.”

Here was Bill Foster’s true frustration: he had utterly lost the plot. Or, perhaps, like Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman, he’d never quite found it in the first place.

Douglas has said this is his favorite performance of his career, and it’s not hard to see why.

Another of my favorite films, The Royal Tenenbaums, gives us the other, triumphal side of the story.

Royal Tenenbaum (played by Gene Hackman) is a charming serial con artist, a spinner of false narratives who, having fathered an epically dysfunctional family, now lets them down over and over again. He is a man tragically in search of his own story — until suddenly, incredibly, he finds it. In the midst of scamming his family yet again, he abruptly discovers his own sincerity and eventually wins them all back.

In the end, he is able to step into his own epic and live it fully — even has it inscribed on his tombstone:

“Royal O’Reilly Tenenbaum, 1932–2001 — Died Tragically Rescuing His Family From The Wreckage Of A Destroyed Sinking Battleship.”

Which wasn’t literally true, of course … but true in every way that mattered.

My February wish for you:

That you take a little time every day to look at the story you’re living and the hero at the heart of that story.

About the writer

John Barth is often mentioned in the same breath as Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, Vladimir Nabokov, and even James Joyce. He has been called “one of the greatest novelists of our time” (The Washington Post), “a master of language” (Chicago Sun-Times), “a genius” (Playboy), “perhaps the most prodigally gifted comic novelist writing in English today” (Newsweek), and “a comic genius of the highest order” (The New York Times).

He won the National Book Award, grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

And yet, he has also been routinely misunderstood. Or perhaps more accurately, to use a George W. Bushism that Barth himself would doubtless appreciate, he has at times been misunderestimated.

Born in 1930, John Simmons Barth grew up in a coastal Maryland town that could have been drawn from a Norman Rockwell painting. His father ran a candy store and was a locally renowned raconteur, much in demand for his story-telling and especially his jokes.

Whitey Barth’s shop (“a small town soda fountain,” as Barth described it) also stocked a range of paperbacks, including works by Raymond Chandler, James. M. Cain, and H.P. Lovecraft, as well as Faulkner’s scandalous Sanctuary and John Dos Passos’s modernist Manhattan Transfer.

Young Jack inherited his father’s eclectic appetite for reading along with his famous sense of humor.

In college Jack majored in journalism, but the flat who-what-when-where-why of reporting didn’t appeal to him. He was also required to take a class in poetry or fiction, so he opted for fiction, and quickly realized he’d found his calling.

In the library stacks at Johns Hopkins University he fell in love with history’s great storytellers — Homer, Virgil, Scheherazade, Cervantes, Dickens, Twain, and others. As he later recalled:

“My apprenticeship was a kind of Baptist total immersion in the ocean of rivers of stories.”

He began to write, and never stopped. (And by the way, remember that phrase, “the ocean of rivers of stories”; it’ll take on more meaning shortly.)

Fresh out of college Jack took a teaching job at Pennsylvania State University, and as he taught he began penning the manuscripts for his first two novels. The first of these, The Floating Opera, was promptly rejected by six publishers. Now supporting a wife and three children on a meager teaching salary, Barth felt the economic pressure, and was immensely relieved when the seventh publisher bought his book — and even more so when the book was nominated for a National Book Award.

The Floating Opera (1956) was followed by publication of his second manuscript, The End of the Road (1958), and then, in 1960, The Sot-Weed Factor, a huge, sprawling comic novel in the style of 18th-century satirists. Bawdy, laden with puns, and dizzyingly complex, it follows the progress of a “sot-weed factor” (tobacco peddler) who travels through a sinful late-17th-century world with his twin sister and tutor. (Barth himself had a twin sister, Jill; his writings often featured versions of his own life story.)

Sot-Weed was a smashing success, and a string of further triumphs followed, including Giles Goat-Boy (1966) and the 1968 short story collection Lost in the Fun-House. In 1973 he was awarded the National Book Award for his novella collection Chimera.

The quote at the top of this email hails from one of those early works, The End of the Road, in which a student named Jacob Horner suffers bouts of paralysis caused by a condition Barth calls “myopsis”: a disorienting worldview caused by the temporary inability to perceive oneself as a character in one’s own life story.

The solution, supplied by a physician who treats young Horner, is “mythotherapy,” a treatment that shows the patient how to identify and assume a clear, central role in his own story.

It was an idea Barth returned to again and again, for example, in his Once Upon a Time (1994): “each of our lives is a story-in-progress … [which is] the mother of all fiction.”

All of which poses an interesting question: What exactly was John Barth’s own life story?

And here is where the misunderestimation begins.

The most common view goes something like this: Barth was an “experimental” novelist who peaked more or less at the start of his career, that handful of early works greatly overshadowing his later output, which never quite measured up to the earlier stuff. He was a “post-modernist” who wrote “meta-fiction.” A product of the sixties.

But that pigeonholing, however convenient, isn’t Barth’s own story. As Barth himself saw it:

“I’m not a very consistent fiction writer (my books don’t resemble one another very much) … I have an ongoing curiosity about what will happen next.”

For example: Barth is widely cited for his 1967 essay “The Literature of Exhaustion,” which is often summed up as a pronouncement that “the novel is dead.” But we rarely hear about his 1980 follow-up essay, “The Literature of Replenishment.”

Despite his reputation, Barth never sought to “kill the novel”; on the contrary, he dedicated his life to reviving, reworking, enriching, and contributing to fiction’s evolution. He was prolific throughout his career, producing a string of novels, story collections, and essays that spanned six and a half decades and publishing well into his nineties, constantly reassessing and reinventing himself.

As one commentator put it in the LA Review of Books, a few weeks after the author’s death in 2024,

“We remember far too much of Barth’s early work; we do not remember enough of what followed.”

In an interview in 2008 the writer made this comment:

“It doesn’t matter to me if critics find that the things I’ve written recently don’t measure up to some earlier book. Now, I’m writing for my own pleasure, and, I hope, the pleasure of some readers.”

As a teacher, “JB” was enormously influential, both revered and beloved by generations of students whose careers he consistently supported, offering feedback whenever asked, unfailingly contributing blurbs to their published works, hosting gatherings and holding forth whenever asked.

Throughout his career he continued leading a course for undergrads called “Rudiments of Fiction,” not only to help raise new generations of writers but for the sake of his own development as a writer.

“Teaching that class gave me a chance to think about first principles: What is a story? What is fiction? I liked thinking about those sort of things at least once a week.”

His writing, it is true, can be baffling at times. It is certainly complicated: full of literary allusions, puns and verbal pratfalls mixed in with profound philosophical discursions, mind-bogglingly convoluted sentences that seem to run on forever, layers and layers of complexity folding in upon themselves.

Perhaps his most famous literary definition goes like this:

Plot = the incremental perturbation of an unstable homeostatic system and its catastrophic restoration to a complexified equilibrium.

… a definition that in its 16 words contains all that made Barth Barth: his love of intricacy, extreme erudition, and absurdist, self-deprecating humor, poking fun at academics while in the midst of being one himself.

As a Maryland neighbor once observed:

“It seems like Jack takes 10 pages to tell something that could be told in one.”

Remember that “ocean of rivers of stories”? Here is a big fat clue to understanding and appreciating his work:

John Barth grew up in and lived his entire life in the Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the country, an environment he loved with unflagging devotion.

In fact he referred to himself as “a kid from the swamp … with the swamp still on my shoes.” As one obituary declared, “with John Barth’s death, the Chesapeake has lost its poet.”

Barth wrote about the Chesapeake again and again — but he didn’t just write about it. In many ways, his writing embodied the Chesapeake. His prose runs less like the course of a river and more like an elaborate, complex network of tributaries, rills, runnels, and rivulets — not so much a stream as a dense ecology of narrative.

The Chesapeake was John Barth’s superpower.

“I start every new project saying, ‘This one’s going to be simple, this one’s going to be simple.’ It never turns out to be. My imagination evidently delights in complexity for its own sake. Much of life, after all, and much of what we admire is essentially complex.

“There are writers whose gift is to make terribly complicated things simple. But I know my gift is the reverse: to take relatively simple things and complicate them to the point of madness.

“But there you are: one learns who one is, and it is at one’s peril that one attempts to become someone else.”

I love that last line so much that I‘ll repeat it here:

But there you are: one learns who one is, and it is at one’s peril that one attempts to become someone else.

Amen, brother Barth.

Recommended Reading

If you’ve never read any Barth, here are some suggestions for where to dip your toe into the water:

The Floating Opera (1956), his first novel and an excellent entry point.

The Sot-Weed Factor (1960), his bawdy, brilliant colonial epic.

Lost in the Funhouse (1968), metafictional stories that helped define postmodernism.

Let me know if you read any of these and fall in love!

Is there a book in you, waiting to be written? A story you’ve been wanting to tell, an expertise you need to share? Consider joining our community of writers in my one-year coaching program, Writing Mastery Mentorship.